Baltimore Neighborhoods Indicatory Alliance Program Manager Matthew Kachura (Image Source: University of Baltimore)

Baltimore Neighborhoods Indicatory Alliance Program Manager Matthew Kachura (Image Source: University of Baltimore)

Today, we Talk To St. Ambrose have posted our second interview of our “Talking with the Experts Series,” and we are honored to host Program Manager for the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicator Alliance-Jacob france Institute, Dr. Matthew Kachura. As many of you already know, Dr. Kachura is a hugely respected community member and activist on behalf of Baltimore City. He is likewise a pre-eminent scholar in the areas of housing, community economic and workforce development, and other issues affecting urban communities. Dr. Kachura recently conducted an innovative study examining the effects of foreclosure on Baltimore’s schoolchildren, which gained much deserved local and national attention, as it remains one of the only empirically-backed projects studying the residual, far-removed affects of the foreclosure crisis. Dr. Kachura has also conducted influential research on the Baltimore Empowerment Zone, the earned income tax credit, and commuter issues, among many others.

Again, we are honored to host such an important and distinguished scholar and community member. My interview with Professor Kachura is below.

Harsha Sekar: It was fascinating to read the results of Phase I of your study on the effects of foreclosures on Baltimore’s schoolchildren. For me, one of the study’s most salient implications concerned the interrelationship of social problems. It appears that public policies that encourage affordable housing will not be effective without the implementation of a broader welfare state, as widespread access to decent housing seemingly cannot materialize without strong neighborhoods, schools, and access to healthcare. Given the findings of your study, can policymakers effectively curtail the problem of inadequate housing without simultaneously addressing the needs of other, related social institutions?

Matthew Kachura: The short answer is no. I believe that urban issues, whether it is affordable housing, high unemployment, social ills such as crime, or issues relating to education, are all interconnected and that policies that take into account this interdependency need to be created and implemented. Trying to address one issue without recognizing that there are a host of other issues related to it will not lead to sustainable or long-term improvement.

HS: Following up on the last question, what are some of the other, less obvious residual effects of foreclosure that you have noticed in your work?

MK: I think a non-obvious issue is exactly what we set out to identify. Little attention has been paid to the smallest victims of foreclosure – children. It is not just that children are also victims of foreclosure, but that the increased mobility resulting from foreclosure can have lasting, long-term effects on their social and personal development and educational performance. These negative impacts might not occur in the year following the foreclosure, but research has shown that missing days of school as a result of having to move can lead to an increased chance of a student dropping out of school, not completing their degree and in the long run earning less income.

HS: Your study also catalogues the disproportionate effect of foreclosures on minorities. While many commentators have discussed this issue, few academic studies document this phenomenon with empirical data. How has the foreclosure crisis functioned to reinforce systemic racism?

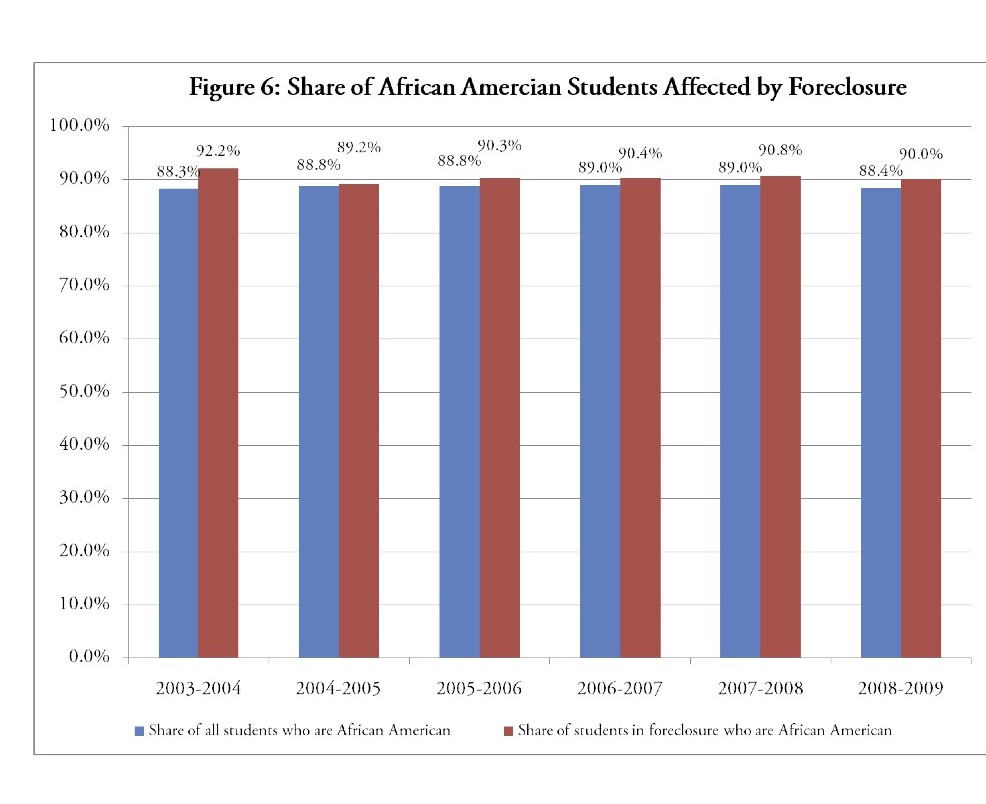

MK: We found several interesting findings as a result of this analysis, including the largest numbers of students who were affected by foreclosure in Baltimore City were African American. This was not surprising though since two thirds of the residents of Baltimore City are African American. There were two other important findings. First, the share of Hispanic students impacted by foreclosure had been increasing to a point where the share of students impacted by foreclosure was the same as the total percentage of students attending the City public schools. Second, we believe the share of white students impacted by foreclosure was not accurately counted, potentially being significantly undercounted. According to American Community Survey data, nearly a quarter of the children in Baltimore City are white but only 8% of children that attend the City public schools are white. This means that these students are attending other schools – most likely private schools – and were not included in the analysis. Overall though, the fact that African American residents and their children were affected by foreclosures in such large numbers supports the facts that predatory lending policies and sub-prime loans were targeted to those persons who could least afford to lose their home. The loss of the home, the primary vehicle to building wealth for many of these families, only perpetuates a vicious cycle of poverty.

HS: At Mayor Rawlings-Blake’s recent Vacants to Values Summit, the market-drive notion of “Code Enforcement” was promulgated a means to reduce blight in the city, which would impose sheriff sales on properties that do not meet the city’s code. How do you feel about this tactic, and what other policies do you advocate to incentivize property owners to invest in Baltimore’s underserved neighborhoods?

MK: I believe that the Mayor’s plan has merit and there have been a variety of other strategies taken in an effort to reduce blight and to turn vacant housing into occupied housing. There are issues with using code enforcement including identifying and locating individuals to serve them with the necessary paperwork, issues relating to selling the properties at Sherriff sales, and then trying to turn them into occupied properties. Many of these properties are so beyond being able to be lived in, they will require significant repairs and persons willing to take the time and expense in making the repairs before anyone can live in the property.

I also believe that there are already a number of policies that are making strides in having residents invest within Baltimore’s neighborhoods. Among these are live where you work programs, which also encourages employment, Healthy Neighborhoods, and the Neighborhood Stabilization Tax Credit. I also believe that the City’s use of data and its Housing Typology model supports the use of strategic investment – targeting neighborhoods with the types of interventions that are needed most within those neighborhoods instead of spreading resources too thinly across a variety of neighborhood types. Most of all, I believe that residents living in Baltimore’s neighborhoods are the best means to encourage other residents to invest and live in Baltimore City.

HS: Much of your scholarly work examines economic development in urban areas. How have established NGOs like St. Ambrose contributed to economic development and vibrancy in the Baltimore area over the past few decades? What do you feel is the role of NGOs in stimulating economic activity relative to that of the city government and the private sector?

MK: NGOs are a critical component to the overall continued health, vitality, and improvement to Baltimore City and its neighborhoods. NGOs have been recognized as an important partner in economic development strategies that cities, such as Baltimore City, rely on for their ability to produce results and make an impact. With fiscal constraints and the need to provide the same if not improved services for a shrinking residential base, NGOs have become a more important partner that the City has embraced to push economic and workforce development. NGOs typically can operate without the bureaucracy and red tape that government agencies have in place, making them, in many cases, more effective and efficient in creating job opportunities and in neighborhood vitality.